Virtual Teaming: Jen's Experience

Why Virtual Teaming is Tough ... and Worth It

I have had the opportunity to team-teach pretty often in my career, including a journalism course with a broadcasting faculty member, in which I took lead on print work and he taught camera operations. I have also taught a Representations in Girlhood class with a literature colleague and team-teach an Online Publishing course each spring with a faculty poet. But this wiki project was different. Being physically separated from your teaching team is a real challenge, but one I am glad we took up and one that I would encourage others to try.

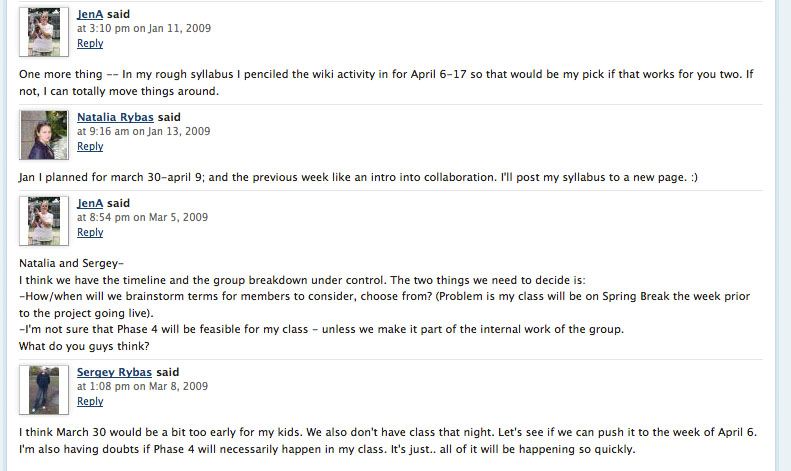

Collaboration is never easy. Even when working with friends and colleagues, miscommunication, scheduling snafus, and competing goals can cause problems. Early discussions of something as simple as what three weeks we could all carve out of our schedules (see image below) were difficult as we worked to find commonality in different courses and universities.

One of the reasons so many of us like collaboration in the classroom is that it fosters—maybe forces—not only team work but also a clear vision of one’s overall project and goals. “Collaborative team members must … do their part to articulate their own understanding about the team’s composition as it is and as it could be,” according to Anne-Marie Penderson and Carolyn Skinner (2007, p. 42). In our case, the “composition” was three separate syllabi and accompanying assignments and activities. It was, of course, our hope that students would experience this same sort of metacognition regarding writing and multimodal composition, but this chance to articulate my own teaching goals and expectations was an unexpected and beneficial side effect to this sort of collaboration. This forced recalibration of my own class planning not as a solitary decision-making activity but rather as “an elongated conversation whereupon users talk to each other to achieve common goals” (Gerben, 2009) was a difficult but necessary part of viewing myself as a member of a virtual teaching team.

As a teacher it is easy to feel part of a team—as a member of a class, a discipline, a department, or a face-to-face project. Higher education is its own discreet discourse community. I see this sort of wiki project as a way to build a discourse community in action. Tyrone Adams and Stephen Smith (2008) took up this concept in their collection Electronic Tribes. Though “tribe” is a concept fraught with troubling associations with colonization, sociopolitical struggle, and overly general anthropological ideas, their definition of an e-tribe as a “narrowly focused, network-supported aggregate of human beings in cyberspace who are bound together by a common purpose and employ a common protocol and procedure for the consensual exchange of information and opinions” (p. 17) is a useful term in bridging the gap between the discourse communities we understand in composition studies (Bizzell, 1982) and the virtual teams featured in business and communication studies. Regardless of the exact terminology, honoring the power of technology to foster community and connection is key. “Our goal should never be what technology can teach us,” Chris Gerben (2009) reminded us, “but how using it and discussing it can help us produce our own community-specific knowledge that can be used with or without a computer.” The goal of this wiki project was not just to gain facility with multimodal composition, but also to create true communities of learners and teachers that participate in and produce knowledges for themselves.

Building communities—be they between the faculty or students—seemed like it would happen naturally in this wiki space, but this project taught me about the need to honor conversation and socializing. While some educators and professionals find that “writing on a wiki facilitates more formal, topic-centric, depersonalized interaction” (Warschauer & Grimes, 2007, p. 12), I found the opposite to be true. While the tone in this work/social space was different than some in-class blog or Blackboard discussions in that it seemed largely focused on the work at hand, I also noticed students used the space to comment on their fears concerning new technologies, worries about busy class schedules, and friendly chit-chat. “The first lesson that Web 2.0 technology teaches us, then, is that no data … is ever useless,” because, as Gerben (2009) said, “conversation is writing is text is data.” It seems that so often we spend time encouraging students in our classrooms not to use new media tools to be social, but in this space and this project, building collegiality and a certain comfort level with team members scattered across the country was a necessary first step in equipping students to complete the assignment. It was also necessary in reorienting the faculty crafting the assignment as we shifted from individual teachers to members of a teaching team.

This redistribution of agency and power among both students and faculty, rather than flowing from faculty to students, led to successes and challenges. The students involved in this project were frequently frustrated by the purposeful openness of the assignment. As instructors, we felt it was important for them not only to actively build community but also to actively shape their response to the assignment. We hoped this less-scripted engagement with the problem might model workplace writing behaviors and also encourage team members to seek consensus and agency from within their group rather than from the instructors.

This shift in power and in some ways a loss of control was a little unnerving to me at first, truth be told. Ann M. Bomberger (2004) relayed her own frustrations and ultimate success with online discussions in a “contentious” (p. 203) class centering on race that shifted power from the private, face-to-face spaces of the classroom to a public online venue. When a student in the course questioned both Bomberger’s opinion and use of terms related to the class in an online discussion, she reported, “I was well aware of two sections of the same class looking on as he challenged my authority” (p. 205). Although our project never faced such open controversy, the reality is that online spaces like wikis do decenter power in such a way that classroom management styles, faculty planning, and strategies for guiding discussion must change and these changes can be unsettling for those of us accustomed to more control in our classrooms. It is a challenge, but one that taught me to trust myself, my fellow instructors, and our students.